TMA 293 Portfolio

The Observational Mode

Oct. 6th 2025

Observational film was among the most popular modes of cinema in the early days of moviemaking. Why is that? Some might argue it’s because it’s the least artistic. After all, you can essentially set up a camera and record someone doing something and call it “observational.” But can you?

Dziga Vertov proves the complex merits of the observational mode through his dynamic choices of film and the immense amount of meaning he creates through it. He shows an image of a large group of people, then places an image of himself with his camera as a giant form in the midst of this scene. Some might argue that this changes the form of the film from an observation to something else; however, it still maintains the elements of observing people's daily lives, which qualifies it as such. This scene illustrates how much meaning can be made within the realm of observational films, despite there being no apparent storyline in many of them. The giant image of the cameraman in the crowd could give us the conclusion that this literal bigness must translate to something figurative. Perhaps the cameraman has so much influence and power through his ability to portray others how he or she likes.

In addition to manipulations to the film, Vertov creates meaning by capturing some of the most tender parts of human experience, starting with the birth of a child. He both shows the pain the mother is going through and the nurses taking the baby away, then bringing it back to the mother to bring the audience into the moment with them and that moment of high intensity. But he also gives us moments of rather low intensity, such as people walking down a street, and presents them in a way that creates a high, chipper pace. He does this through quick, rapid cuts, and it snaps the observer's attention to the screen.

So, we now see that there is great potential to create meaning in observational film, and engagement is similarly very much within the reach of a skilled filmmaker. So why don’t we start making observational films? Right now? My personal roadblock is access.

Getting legitimate permission from someone to film them today takes a hefty contract for the individual to sign and read through. This takes time and is especially difficult when you’re hoping to film people in their natural walks of life. So how do we go about this? I am not entirely sure. Perhaps we film people at a further distance so their faces aren’t distinguishable? This is common with overhead shots of metropolitan cities with masses of people walking to and from their workplaces. But part of observational film’s charm is in its intimate witnessing of people up close, often in unexpected ways. For instance, in Man with a Movie Camera, we see him in his darkroom assembling the film strips for his movie (this movie). This is, of course, staged, but it shows us an intimate glimpse of his meticulous process. He sets up the camera, then films the film strip editor doing his work. Today, this requires access to the editor and written permission from him.

Perhaps it is the issue of accessibility that results in a lower number of observational films being produced today. When it first began, there were few laws about privacy, so early filmmakers often filmed (perhaps they shouldn’t have) people in public without their express consent.

Despite the observational mode’s lessening popularity on the production side of film for the reasons discussed, it still has great potential to create new meaning.

Act of Killing and Night and Fog

Oct. 15th 2025

Both the Act of Killing and Night and Fog can be categorized as reflective prosecutor films. Both films reveal truths about massacres through showing, rather than telling their events. However, the way they showed these atrocities differs. While Night and Fog aims to reflect on the aftermath of the devastation via wordless images of tragedy, the Act of Killing chooses to embark in a more active retelling of a story through the eyes of the perpetrators, creating a narrative-based film with narrative arc surrounding the perpetrator’s experience.

First, I will discuss how both films aim to show, rather than tell, the atrocities in both respective genocides, and how this technique elevates the empathy the audience feels for these tragic events. In Night and Fog, Alain Resnais shows footage of shoes. Thousands upon thousands of shoes. Without end. He could have said, ‘millions of Jews were killed,’ but that’s just a number. Or interviewed someone describing their tragedy, but that isn’t the same as a witness. Through showing the shoes, Resnais urges the audience to actively imagine who those shoes belonged to, and put this within the context of the greater story. He didn’t push an ideology upon us per-say, but rather showed us the reality, as a reporter is supposed to do according to Barnouw, and we are able to make a judgment based on the reality shown.

Similarly, the Act of Killing director Oppenheimer chose to have former “gangesters” (perpetrators_of_the_genocide) re-enact their killings. Near the beginning, Congo is on the roof of a building and demonstrates when and where people were killed. It is through this tangible action that us as an audience understand conceptually what went on. One could read a description of how people were killed, and be horrified. But to see it, or at least versions of it, the audience witnesses some of the ugliest sides of humanity without any way of hiding from it. Descriptions void of life can give context, yes. But Oppenheimer has them re-create these scenes in an effort for both the audience and his subjects to see, witness and more fully understand.

The similar reporter style of filmmaking which both films emphasize by showing the events rather than telling their thoughts on them creates a sense of immediacy and urgency in the watcher. It snaps their eyes open, letting them take in an image that changes their perception forever.

Night and Fog creates a more reflective tone when compared to the Act of Killing due to a lack of consistent characters and sparse dialogue. Rather than participants conversing about the events, the audience is left to witness and confront them themselves. However, Barnouw does say that “the impact is intensified by a quietly reflective, powerful commentary written by Jean Cayrol” which goes to show the power of including few yet powerful words. Night and Fog its both investigative and reflective, as it exposes us to social realities and pushes us to question our world through these realities. It introduces images that don’t line up with our perception of the world. In the context of Night and Fog this is through the portrayal of shoes (in the image above) which forces the audience to re-imagine or even re-construct their perception of the very world they live in.

The Act of Killing similarly creates a reflective feel, but because Oppenheimer uses narrative form to do so, the audience has slightly less time to reflect and more time to follow the story. We watch as Congo reenacts his killings, and eventually becomes appalled by himself. On the very roof that he killed countless people, the realization of what he did hits him, and he throws up. Throughout the film he grows increasingly uneasy, showing the narrative arc of increasing conflict, until the climax, where his heart changes, or perhaps his perception of himself is so appalled by his actions that his body rejects his very insides. The reflective nature picks up especially near the end, when Oppenheimer slows the pace and leaves more non-verbal scenes. This guides the viewer in Congo’s reflective journey, which introduces difficult dilemmas regarding the ethicality of redemption among the perpetrators of a genocide…

My filmmaking approach was modeled after Green Gardens, with an aim to be as observational as possible without interfering with the moments. However, like Green Gardens, the people I was filming seemed to like to talk to me, sometimes giving me some of the best footage in those moments.

Nichols chapter 9 discusses the aim of observational mode as a way to capture life without interference to whatever extent possible. In class, we discussed how this might not be possible, due to the observer effect. Perhaps our presence will always impact our participants behavior one way or another, simply by knowing that a camera is in the environment. This was certainly true for my case of filming, however with time they relaxed.

Nichol goes on to explain how the observational mode emerged in the 1950s/60s in part because of the smaller cameras which were hitting the market. I used a Sony A7 iii to shoot this, with a 50 mm prime lens and a small shotgun mic. This light camera set up was ideal for moving around and getting in the moment shots. If I were to go back in time though, I would have used a gimbal to steady the car shots.

As much as possible, I tried not to stage events. I tried to film things in real time, as they occurred. My biggest constraint was the 2-3 minute timeframe. Each scene could have been stretched out to several minutes with this mode, so I had to make some decisions with quick cuts, like the one of Than and Clara walking away from the car, appearing to be less in the moment and drawn out as we would typically see with observational films.

Was this a true representation of reality? I feel it was a representation of a moment in reality, yes, however no moment or set of actions is ever the same as the next. To assume I captured the real version of Than and Clara and their relationship would be inaccurate. I simply observed them for an evening which was, like all other evenings, unique. In the preface that every moment is unique, I would argue there is no way of capturing the full essence of any individual or relationship. The world is far too complex.

Doc Mode Activity 1 Observational Mode

Online Response 3

Nov. 8th 2025

The reflexive mode offers a greater image into both the subject and the crews’ ideologies and thoughts, whereas the participatory mode gives a more genuine image into the everyday life of an individual. Not one mode has more truth than the other, but rather both express different types of truth. Reflexive mode can better express complex ideas and themes in an organized manner, while the participatory mode can open the doors to the truth of the outside, lived world. Reflexive seems to be more psychological and internal, while participatory external and lived.

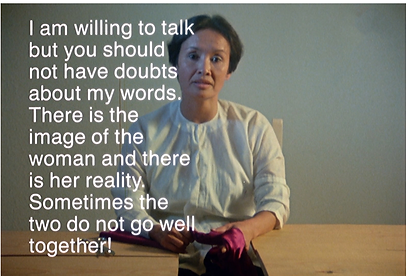

Surname Viet, Given Name Nam is a slow, highly scripted exploration of a series of women' s experiences in Vietnam. It has a calculated performance, and includes scenes where women talk about making the film and being in it. It expresses the complications of dislocation and exile and the strength of Vietnamese women through scripted hand movements, gaze directions, and pauses in speaking. Much of what we see in this film would never occur in real life, and the film acknowledges the artistic created nature of this film through the scene near the end where the women are discussing making the film with each other outside. This reflexive element, reminded the audience that they are watching real people, with real lived experiences, to increase receptiveness towards their deep ideologies presented.

One of the women talks directly to the camera during some of the interview, as the photo I provide illustrates. This helps open the audience's gaze towards not just her actions or her appearance, but rather to her thoughts and feelings. This slow pace, perhaps much slower than even real life (or so it felt), helped give the audience space to think and consider the words she spoke, bringing out further levels of empathy. The close ups on hand movements we see throughout the film help represent an element of insecurity that these women may face – an internal emotion – which is a key goal in reflexive documentaries.

Sherman's March gave us a glimpse of his outside world. What he looks like to others. In the film, we would watch the awkwardness of his interactions and experienced them as they happened. The participatory mode felt, in this film, lighter and lower stakes, compared to the heaviness and intense gazes from Surname Viet, Given Name Nam. It did, however, offer us a better glimpse into the lived life of Ross. The image attached below illustrates how we see what Ross sees throughout the film, and experience relatively unemotional straight-forward way. There wasn’t a grand presentation of emotional buildup in this movie which some would attribute to it being more true-to-life than Surname Viet, Given Name Nam’s emotionally weighted presentation of ideas.

In Lyra, Allison Miller uses both Reflexive and Participatory documentary modes. Miller chooses to include videos of Lyra, the main character whose life is commemorated, film herself and edit her own videos. The irony here is that those videos that Lyra is seen filming (such as the one below for her personal youtube blog) and the time editing them wasn’t for Alison’s film at the moment of production, but for her own professional aspirations. Despite this, we still are exposed to the process of creating a film, and the thought provoking reflection that this creates. It gives Lyra more depth and activeness in her very person, illustrating her as the one who is forging her future and her identity. Through this reflexive nature of filming herself for youtube, including un-published drafts, we are able to see glimpses into Lyra’s behind the scenes ideologies of wanting to promote justice through her work, to the extent that she is going to craft these videos to that end.

Allison Miller goes and talks with some of the family members, while keeping the film rolling. She often does participatory-style videography in her work. An example below is of a family member of Lyra crying, as she talks with Miller, the director. This scene gives us a more raw and genuine look into the real emotions of that movement, but doesn’t necessarily present us with a large theme or idea for us to decompress. It’s experience-based and moment-based, bringing out the reality and truth of those few minutes there.

I created two films for this assignment, as I was unsure if we were allowed to use archival footage or if all footage needed to be shot in our present day. My first video (the second listed here), was shot in Morocco while hiking Mount Toubkal. In it, I interact with 2 individuals, one I knew from the hike and another I met just then and knew for a total of 30 seconds. The second video (the top one listed here) follows me and my roommate as we prepare for and enter a friendsgiving.

Both films include me, the filmmaker, interacting heavily with all the participants in my immediate space. Similar to Sherman's march, I tried really hard to talk even if it would be awkward. In the friendsgiving video, I entered the home of the host and was highly nervous as I was bringing a camera into someone’s apt unannounced, but people seemed to be much more accepting of this than I expected which led me to sound and act more relaxed, making the film portray a more confident version of myself. It didn’t end up feeling as out of place as it may have during Sherman’s march.

Other such participatory films could include The Salt of The Earth, where the filmmaker interacts with his father, a famous photographer, throughout the film. He included himself in the film to help the audience connect more with him as a storyteller. I feel both the Friendsgiving short and the Morocco short gave a focus to my physical voice as a human, which may have helped show a bit more about who I am as a filmmaker. In the Friendsgiving film it demonstrated that I knew something about cooking, while in the Morocco film this mode helped demonstrate my knowledge of the Darija dialect of Arabic.

The idea of truthfulness was a point of debate in both our class discussions and our readings. What documentary mode is the most truthful? And in what type of truth are we discussing? I believe that participatory documentaries are truer to the voice of the filmmaker than most. In other modes, like performative, the filmmaker can manipulate the lighting, pacing, subject choice, and more in order to create a feeling and tone however they would like. In Participatory films, the Director is forced to contribute to the screen-time itself. You can’t escape showing who you are when you yourself are in the film. Perhaps some might feel like they act less like their genuine self by being in a film, but I felt the opposite during both films, meaning it brought out a greater level of truth in revealing who I am at a human level.

In the Friendsgiving film, I felt that at the beginning it was slightly uncomfortable for my roommate, but over the span of a few minutes it turned into something regular and fun. We were both able to interact in a relatively regular way, of course with both of us probably talking clearer than we usually do to some extent. In the Morocco film, it was a bit of a confidence booster, because I realized my Darija Arabic accent isn’t as bad as I remembered. It reflected the reality, rather than negative self-talk that I may have experienced prior to this, which was an uplifting opportunity for me.

Doc Mode Activity 2 Participatory Mode

Online Response 4

Nov. 23rd 2025

An area of study I engage with is focused on minority groups in the Middle East. This can include the Druze in Syria, Lebanon, and the Holy Land. It includes Greek Orthodox Christian Palestinians in Jordan and Palestine. Chaldean Christians in Iraq and the Kurds in Kurdistan similarly draw my attention. This is not because they are any more important than those of the majority, which include Muslims in the Middle East or Jews in Israel Proper, but rather because they are often ignored. When a minority group is ignored, the majority group writes the narrative of the land, getting away with discrimination and violence. The only way we can take the storytelling power away from the dominant power is through enabling minority groups to represent themselves. Documentary, it seems, is one of the most powerful mediums in which to elevate a minority group's voice internationally because it gives them the power to portray themselves how they wish to be seen. I argue the Performative mode expresses organized ideas and leaves less space for interpretation while the participatory mode includes more genuine character personalities and allows for more interpretations of the subject at large.

Performative mode films can explore ideas in an organized way, without including any unnecessary bits of footage which don’t directly contribute to that main idea or theme. Participatory mode films will include much more footage which some might deem unnecessary to a direct theme or idea, but rather simply shine a light onto who the characters are. Supersize me shot largely in a Performative style, where the main character Morgan Spurlock inserts himself as the main subject and has himself do things for the camera. He eats food from Mcdonalds and acts in ways which are specifically performed for the purpose of this documentary. Through this, he is able to express the direct consequences of him eating via a narrator voice he overlays (his own voice) the footage he chooses to show. As a result, he concisely presents the negative effects of eating in the fast food industry and expresses that idea clearly.

If we apply these ideas into the context of a minority group, it becomes apparent that performative mode documentaries could push a certain ideology or aim of a minority group perhaps far better than traditional participatory films, which often aim to show the day-in-a-life of someone. Nichols describes the performative mode in Chapter 8 as a means to express truths and emotions, both of which are accomplished in Spurlock’s quite tragic decline in mental and physical health, which was performed in performative mode for his documentary.

Performative mode films guide the audiences minds on what they should believe in a more explicit way, while participatory films allow the audience to experience the character of the minority group or underrepresented community. In Tree of Life, Houman uses participatory mode to talk with the stars of an old Iranian film who had since been forgotten and returned to a low-class life. The film never directly suggests any theme, but hints at many, such as the fading of fame. Instead of clearly directed messages, it focuses instead on interactions between individuals presented in such a way that gives priority to the subjects’ voices, whether or not it advances a certain theme or not. It was simply more of an exploration of character, while the Performative mode remains a more structured theme-based project.

@ Houman

Participatory mode can greater show the character of the subjects at hand. In Minding the Gap, Liu shows participatory mode footage of himself and others throughout the film, which greatly enhances how real the audience feels the footage is. It becomes apparent they are not acting for the camera, but rather are interacting with each other. Yes, with an agenda, but regardless they are expressing themselves in naturally human ways, which greatly add to their character. When applied to minority groups, this could help add them to the public's image. If people connect with members from the minority group at a personal level then they will gain international spotlight if their rights are abused.

I created two films for this assignment, as I was unsure if we were allowed to use archival footage or if all footage needed to be shot in our present day. My first video (the second listed here), was shot in Morocco while hiking Mount Toubkal. In it, I interact with 2 individuals, one I knew from the hike and another I met just then and knew for a total of 30 seconds. The second video (the top one listed here) follows me and my roommate as we prepare for and enter a friendsgiving.

Both films include me, the filmmaker, interacting heavily with all the participants in my immediate space. Similar to Sherman's march, I tried really hard to talk even if it would be awkward. In the friendsgiving video, I entered the home of the host and was highly nervous as I was bringing a camera into someone’s apt unannounced, but people seemed to be much more accepting of this than I expected which led me to sound and act more relaxed, making the film portray a more confident version of myself. It didn’t end up feeling as out of place as it may have during Sherman’s march.

Other such participatory films could include The Salt of The Earth, where the filmmaker interacts with his father, a famous photographer, throughout the film. He included himself in the film to help the audience connect more with him as a storyteller. I feel both the Friendsgiving short and the Morocco short gave a focus to my physical voice as a human, which may have helped show a bit more about who I am as a filmmaker. In the Friendsgiving film it demonstrated that I knew something about cooking, while in the Morocco film this mode helped demonstrate my knowledge of the Darija dialect of Arabic.

The idea of truthfulness was a point of debate in both our class discussions and our readings. What documentary mode is the most truthful? And in what type of truth are we discussing? I believe that participatory documentaries are truer to the voice of the filmmaker than most. In other modes, like performative, the filmmaker can manipulate the lighting, pacing, subject choice, and more in order to create a feeling and tone however they would like. In Participatory films, the Director is forced to contribute to the screen-time itself. You can’t escape showing who you are when you yourself are in the film. Perhaps some might feel like they act less like their genuine self by being in a film, but I felt the opposite during both films, meaning it brought out a greater level of truth in revealing who I am at a human level.

In the Friendsgiving film, I felt that at the beginning it was slightly uncomfortable for my roommate, but over the span of a few minutes it turned into something regular and fun. We were both able to interact in a relatively regular way, of course with both of us probably talking clearer than we usually do to some extent. In the Morocco film, it was a bit of a confidence booster, because I realized my Darija Arabic accent isn’t as bad as I remembered. It reflected the reality, rather than negative self-talk that I may have experienced prior to this, which was an uplifting opportunity for me.

Doc Mode Activity 2 Participatory Mode

I went into this film wanting to just create a beautiful canvas of shots I got this summer, but haven't had a chance to work with yet. However, as I got further into the process, I found that much of the footage I had evolved around beer. After discussing with a roommate, I decided to aim for a satirical beer commercial in a poetic style. I will discuss below how this is poetic.

I chose a slow and beautiful instrumental piece to play as the background music, and adjusted the video clips according to the audio’s flow. I at first wanted to explore a theme of belonging and community in a literal sense (before it became a satire). I had many shots of people interacting with each other, and laughing and such, and felt that this could work its way into an interesting theme. However, as I continued forward, I found that there were also quite a few shots showcasing both the ocean and the desert, so I chose to juxtapose those as best I could.

When one of the surfers is preparing his board, I then cut to the ocean. Similarly, when people prepared surf boards near the ocean, I then cut to people sand boarding, further giving contrasting visuals which the viewer can interpret as they’d like.

This film was in no way meant to encourage the drinking of alcohol, but rather it was created simply to express a range of feelings. Friendship, community, and fate. These feelings were communicated through the poetic mode I used, which did not have a particular storyline or aim. Rather it simply expressed feelings through imagery and music.

The film was meant to be more of a mood piece and sensory than anything else. I placed strongly contrasting colors and elements side by side and used transitional scenes. For instance, when transitioning from the mountain to the beach, I use dogs to connect them two. First a dog in the mountain, then I show a dog on the beach. Similarly, I do this with people. If I want to switch the camera to feature another figure, I try to show a shot with that figure and the previous figure featured, as illustrated when the surfer stands up on her board, then I transition to them warming up as a collective, before focusing on the guy doing his back stretch. Through these transitions, I was able to create a more consistent emotional tone in the film and created an element of continuity to follow while experiencing the visuals.

I’d like to thank the surf team for bringing me on to get content for them. Although I only got photos for their use, I also got videos in case the chance came for me to do something with them, which it has at last after far too long. One of the joys and curses of life is finding old footage, and feeling compelled to do something with it. Again, this is not a beer advertisement in any serious fashion, but rather satirical.

Doc Mode Activity 3

POETIC MODE

Between the World and Me and Paris is burning both reflected on the insecurities we feel when we feel vulnerable and exposed. Although in different contexts, they both evolved around discriminated communities which had been mistreated for being authentic, for being themselves. Both the film and the book connect by expressing this vulnerability via genuine time with the individuals, whether that be in coates’s conscious flow or individuals getting ready for a drag race in Paris is Burning.

In Adam, Maryam Touzani exposes us to the insecurities the main character feels as an unmarried woman in Morocco who is pregnant. She does this through long scenes of conversation between her and a baker in Casablanca who takes her in, when nobody else will. It is through genuine time with the individuals where we are exposed to their thoughts, that we are able to observe insecurities from things that are culturally tabooed.

Similar to Adam, Coates’s book gives us genuine time with him as an author, with him talking about the history of blacks, and the injustice that has been placed upon them. He also very explicitly states that a black body is vulnerable, to abuse from others, showing further that when we spend more time with someone via film, literature, or otherwise.

On a similar note, in Paris Is Burning, there were long-cut interviews where the interviewees were simply able to talk and express themselves. In this particular scene, as shown below, the interviewee describes their desire to become famous and also describes their insecurities when dealing with others, especially in romantic relationships. Simply by giving us time with the individual from the individuals in the LGBTQ+ or individuals in the black community is enough to reveal insecurities that are felt.

This can even go as far as relating to qualitative research data done on underrepresented groups in the field of political science. Leila Ahmed does a review of qualitative studies on motivations for the wearing of the Hijab and found trends in her results (Leila, 119). Although this study didn’t point out a particular insecurity, it revealed internal dialogue about a complex issue within the local context, which relates to the two pieces of literature above, both exploring the dialogue, whether vocal or conscious, which are expressed via long stretches of time. The study above panned for years, and was able to get revealing results because of it.

Media or literature or research that reveals the internal dialogue of an individual can effectively open up doors to us seeing their insecurities, vulnerabilities, or cultural context and motivation for certain behaviors. The particular key point that the book and film focused on was the vulnerability of life as a minority, as explored through Coates description of violence against blacks and interviewees’ descriptions of often being shunned by society in Paris is Burning. Ahmed, Leila. “The Veil and the Islamic Resurgence.”

Women and Gender in Islam: Historical Roots of a Modern Debate, Yale University Press, 2011, pp. 117–131.

FINAL PROJECT FILM

Firstly, I would like to discuss my non-fiction film’s relevance to different time periods. In Doc Beginnings II, when we watched Man with the movie camera, we learned about the development of more portable cameras, which allowed for more versatile shots, effectively capturing more genuine human interactions.

My film engages in that same technological advancement of the reliability and portability of small cameras. I was able to bring my camera up to the mountains, and film without largely affecting the scene around me, during the first film shown (my project is a compilation of two films, where I film myself watching them in a theatre with comments and critiques).

Similar to how Nanook of the North romanticized certain elements of tribe, my second film (in the overall film) embarked in similar elements, which was used even back at that time. In Nanook of the North, Flatherty portrayed the tribe as being isolated from the West, using spears instead of guns, and largely being in this romanticized type of existence. However, in reality they did use guns, and were at least somewhat exposed to Western influence. He showed us a certain image that he wanted us to see, even if it wasn’t 100% how people live regularly. Similarly, in my second segment I included footage from a group of surfers on a trip I filmed. This is not an accurate representation of everyday life in the slightest, and could easily be classified as skewing the image of reality for this reason. I selectively chose moments in their lives that were romanticized, leading to the light uplifting feelings produced. Like Nanook of the North, regular day life is not fully represented by the images shown on screen.

In addition to similarities near the beginning of film history, my film touches on some similarities with more (relatively) modern films, such as Sherman's march. Much of Sherman's march is shot in participatory mode, where he interacts with friends or potential partners in an often uncomfortable way. I purposely included some uncomfy tension near the beginning to evoke this same feeling of being in the moment when we weren’t able to start playing the movie. It was fully unscripted. We rented the room, and I tried to set up my laptop, but the video wouldn’t play. Subsequently, my friends got up, waited awkwardly, and we discussed ways to solve the issue. This could have been cut, but I chose to include it to engage in the participatory mode, as I felt it gave a more genuine taste of what it was like for us in that moment.

I also engaged in the performative mode and reflexive mode like in Surname Viet, Given Name Nam. Reflexive elements were of particular importance in this film, as I was hoping to express my wishes and regrets and feedback on the process of making the film, and things I might have changed if given the chance. Throughout much of the film, Trinh T. Minh-ha has the women on screen talk with very specific hand motions and facial expressions in order to convey feelings of insecurity and uncertainty. I too used scripted movements when the camera was facing me, in contrast to the participatory mode engaged in near the beginning of the film. As I had very shaky camera movements, I had a cut scene to my facial expression where I said “oof” as if frustrated with myself for shaking the camera instead of staying steady. Through this snippet of performative mode, I was able to expose the viewer to the feelings I had, and the idea that I was embarrassed from the camerawork. Performative mode has been used to express difficult themes and feelings, as we saw with Surname Viet, Given Name Nam, and I am striving to similarly convey ideas via performative mode as it was done at that time in history.

In terms of reflexive elements, this is what I based my film off of. I wanted to engage in observing the filmmaking process via me discussing the creative choices made and changes I would like to make. Instead of showing actual cameras or lights or the filming itself, I chose to reveal my thoughts and insecurities about the filmmaking process, effectively giving the audience a look into what it takes to make a film, and the choices that go into it. This helped detach the viewer from the film itself, and perhaps attach them more with me, as the narrator, as I am both in the films they view, and the narrator in the (outer) film they are viewing. It’s a paradigm, which forces the audience to use you as an anchor to figure out what is happening. Similarly, in Surname Viet, Given Name Name, the women are shown outside the filming process, discussing the filming process about 2/3rds into the film or so. This gives the audience them, as characters, to rely on as anchors rather than a single storyline or concept they are trying to follow. Through using characters as an anchor when exploring multiple levels of film, more empathy and attachment towards the subjects can follow, as happened with the women in Surname Viet, Given Name Nam.

I made this film to illustrate how the final product isn’t always final. I both showed myself critiquing my own work while watching it and revealed technological errors we encountered just setting up to screen the film for some classmates. I noted multiple films throughout history (time periods) which my film was based off of (or certain elements of it), but I’d also like to suggest that my film can relate to modern day behind-the-scenes films, which have grown in popularity among franchises such as Disney or Marvel. Society today is fascinated by the elements that go behind the created product, if for nothing else to critique it. There is something engaging about seeing superheroes both as the character in film and as the very human actor in the real world film. I engaged in reflexive mode to illustrate that these final products that you often see, aren’t really final. They have flaws, no matter what budget they hold. They will have bits and pieces that directors will go to years later and say “I wish I would have changed that” but they can’t.

In addition to reflexive aspects, I also included poetic elements, especially near the second half of the film. I took Minding The Gap’s intro and outro as my inspiration, where the guys are riding their skateboards around town in the beautiful sunset with moving orchestral music in the background. I felt Bing Liu did a great job at showcasing human relationships and the depth of those friendships through these skating scenes. Similarly, I had many scenes in the sunset, with a group all together spending this special moment. I used orchestral music, like Liu, to help add a more moving element to this scene, in contrast to my light quick paced music when I am scrolling through my class website and clicking play on the videos.

This film was a delight to make. It really helped me as a filmmaker contemplate the choices I made when editing and choosing what to include or what not to include.

About TMA 293

TMA 293 is a class for authentic storytelling through documentaries. We want to enjoy the films we watch and get good at telling stories ourselves!

Get in Touch

For inquiries and screenings, reach out to us at:

Email: info@tma293.com

Tel: THERE IS NO TELEPHONE

Stay Updated